SAFe Survival Guide: part 3— Why Flow is Important

In part one, we discussed how SAFe's commitment-focused approach to detailed planning can trap us into inflexibility, disrupted workflows, and prioritization challenges.

In the second part, we discussed the problem of deciding upon a solution upfront.

In this article, we will discuss why flow matters and the problem of trying to plan around dependencies instead of removing them.

Remember John, who started a new, exciting job at a large company using SAFe? We have already touched on the subject of flow when John's teams discovered that if they fill their backlog 100%, they will not be able to take on unexpected work. Any interruption or extra work cannot be handled because the "glass is already full and can't fit any extra". They experimented with adding slack and only filling their backlog to 70% to handle unplanned work.

Basically, the team experienced disruptions to their workflow because they tried the approach of maximizing their resource utilisation.

Let us discuss the difference between resource utilisation and flow.

Resource Utilization vs Flow

Maximizing resource utilization is a proper approach when we have predictability without surprises. Here, we want to make decisions as early as possible. Here we can make a plan.

Resource maximization and Gantt charts are king when one can anticipate risks and plan for them in advance.

When we can plan, we can manage top-down and break down requirements into details. We can focus on ‘compliance’ and industry standards. Here efficiency is when everyone can execute according to predetermined plans and processes. It works because there are no surprises. So we can push work.

When we have uneven capacity, can’t predict and do not know our capacity, pushing work is not efficient. Here it is better to pull work. Here, flow is king.

Think of a 4 * 400-meter relay. How quickly we can pass the baton is more important than ensuring everyone runs at full speed all four 400 meters. Keeping everyone busy is not the highest priority. Controlling processes and how we work is more important than controlling people.

Iwould claim that working with SAFe never puts you in a predictable world. The reason is that when you scale up and have hundreds of people working together, you never have certainty or predictability.

SAFe tries to handle the unpredictability with more planning – such as marking dependencies with red yarn on a product board. An approach well suited for resource maximisation.

An alternative approach is to

a) fix the constraints and

b) focus on flow.

The DevOps Three Ways and Theory of Constraints can help us achieve this.

How The Three Ways Can Help Us

InDevOps, we have “The Three Ways.” Flow is about making your work flow as fast as possible throughout the process or value chain. Throughout the process we usually encounter constraints that stop our flow.

Feedback is about getting the correct information when needed and doing something about it.

Flow allows us to put something into production fast, and feedback loops enable us to learn. Continuous learning is about learning from the feedback and fixing "things" both now and changing the system to ensure it does or doesn't happen again.

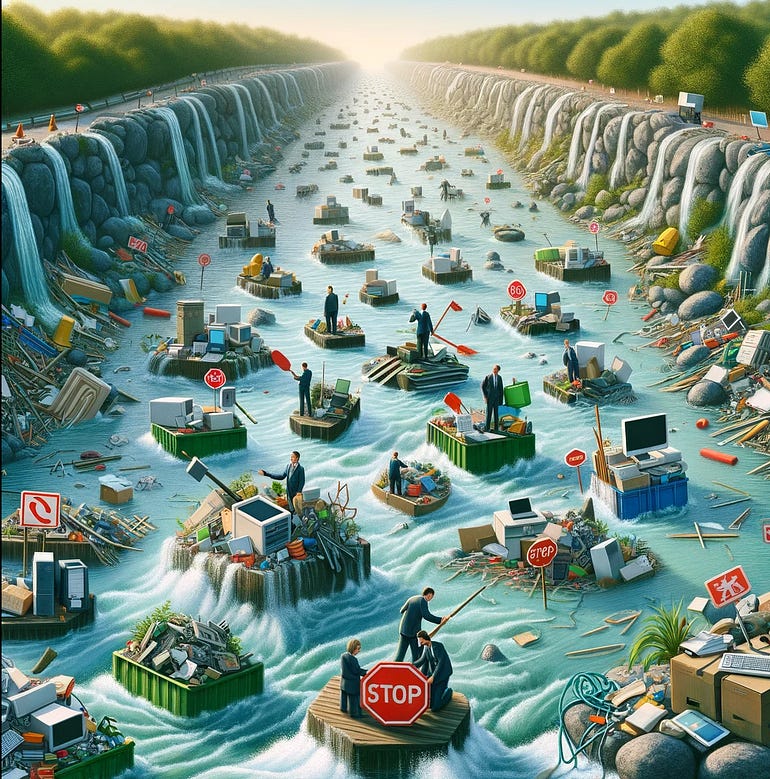

I like to visualize flow as allowing something to travel as fast as possible on a river without any debris, rocks or other dangers stopping the flow.

There are a lot of things that stop our flow in Software development. Dependencies are one of the worst ones.

Now, let's revisit John and see how he encounters problems with flow.

John and the red yarn

One day, John discovered the teams in front of the program board looking at the mess of red yarn. The team struggled with dependencies. Often, teams could not finish their feature because they had to wait for another team to complete their part, which might be the next Sprint. Meaning there was a lot of unfinished work in progress handed over to someone else.

The approach caused delays. When defects were found and sent back to another team, they had to shift focus and try to remember what they had worked on three weeks ago.

This meant constant interruptions. John and his teams struggled to have flow.

As they gathered around the board again, Ted, the Scrum Master, said:

“Why don’t we try to remove the constraints instead of just marking them with red yarn and doing constant firefighting?” Everyone looked at Ted and said he was absolutely right. The team had begun to think of the Theory of Constraints.

John noticed that it is often hard to pinpoint what causes constraints. Waste was everywhere, stopping the flow. One day, a developer came across Poppendieck's seven wastes of software development. They included handovers, over-engineering, and unfinished work. Being able to identify waste helped the teams remove inefficiencies.

As the teams started to remove constraints, they told John that while some constraints were easy to fix and within the team's power, such as automating their deployment process, other constraints were more problematic to fix.

The large organization's complex structure, rules and policies, and complicated landscape of products with dependencies made it challenging for the team to address the constraints. In these cases, SAFe's approach to coordination and planning was a tempting workaround.

The Scrum Masters asked John to create better conditions for the teams. Ted said the teams can become more autonomous with an architecture supporting independence. And please help us remove technical debt so we can have a better developer experience. John promised he would do his best.

My experience tells me we love doing heroics fixing today's problems, but we seldom fix the system. Often, Agile teams do not have the mandate or conditions to change the system.

Why teams are mainly powerless to handle dependencies

From my experience, few teams question the system. Very rarely does the retrospective solve problems outside the team. Often, teams are already effective.

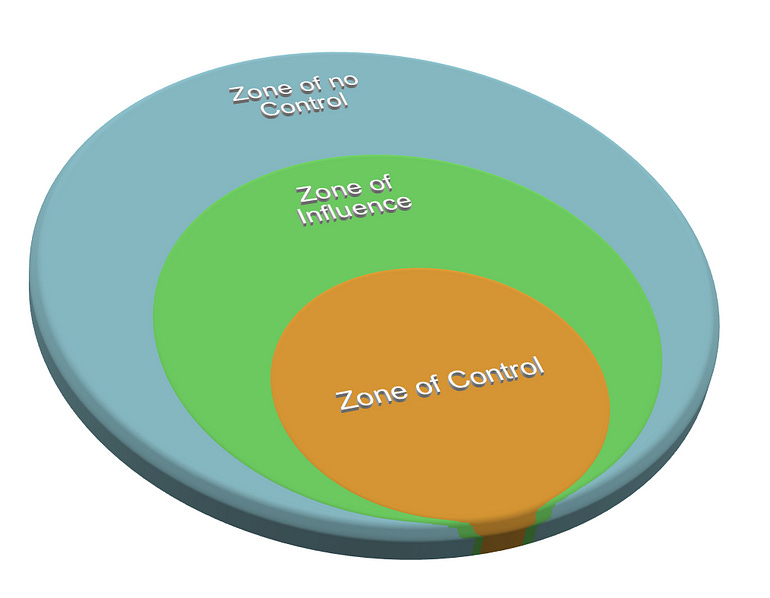

Often, what slows down teams are constraints, waste or dependencies outside the control of the team.

For example, in the story of John, we can divide it as follows:

Zone of Control

Automating Deployment Processes: The team can directly control their internal processes, such as automating deployments to reduce manual errors and speed up delivery times.

Adopting Practices to Reduce Waste: Implement practices to mitigate the seven wastes of software development, as identified by Poppendieck. These include reducing partially done work, extra features, relearning, handoffs, delays, task switching, and defects.

Zone of Influence

Educating Product Owners on Technical Debt: While the team might not have direct control over prioritization decisions, they can influence product owners by educating them on the importance of addressing technical debt, thus indirectly affecting decision-making.

Promoting Architectural Independence: Although directly designing and implementing an independent architecture may fall within their control, influencing the broader organization to adopt these principles requires persuasion and advocacy.

Zone of No Control

Organizational Structure, Rules, and Policies: The large organization's complex hierarchy and established policies are beyond the team's control. These factors can significantly impact the team's ability to make swift changes.

External Dependencies in Product Landscape: In a large product landscape with intricate dependencies, the team cannot control the timelines and priorities of other teams or the legacy code that enforces specific dependencies.

Inherent Constraints within SAFe: While SAFe offers mechanisms for dealing with dependencies and coordination, some limitations of the framework, regarding flexibility and responsiveness to change, might be beyond the ability of any single team to alter.

The bottom line is that we should change the system, not the team. Teams are usually excellent.

Itis a shame that often when a team suggests a change in the way of working, the organization resists the change.

Usually, management resists, believing the way teams work should be standardized. This is an old factory way of viewing, believing that standardization, minimizing variance, and optimizing work processes will improve efficiency.

This approach works well when you have simple, repetitive tasks. However, it works less well if you want autonomy, creativity, and innovation.

This is a shame, as only management can change the system and what is outside the team's control. The result is that the teams feel powerless, unmotivated, and cannot be autonomous.

What to do and what to avoid

Below are a few suggestions on how better flow can be achieved.

Avoid:

Workarounds for Dependencies: Don't plan around dependencies. Fix them! Instead of beating around the bush, aim for systemic solutions that remove the constraint.

Waste: It is often hard to identify waste in your processes, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t. If not, you are only working harder, not smarter. Removing waste is necessary for flow.

Underpowered Teams: Teams lacking authority, tools, or skills are a recipe for bottlenecks and frustrations. Empower teams with the resources and autonomy to make decisions and carry out their tasks effectively.

Try:

Learn to identify waste: these wastes (overproduction, waiting, transporting, inappropriate processing, unnecessary inventory, unnecessary motion, and defects) can be adeptly applied to software development. Removing waste can dramatically improve the flow and reduce cycle times.

Theory of Constraints: This management philosophy aids in systematically identifying the most significant limiting factor (constraint). Once removed, you look for the following constraint. Over time, the flow will improve.

Automate as Much as Possible: Automation is the key to consistency, reliability, and efficiency. It eliminates human error, frees up valuable developer time, and ensures that repetitive tasks are done swiftly and accurately.

Architecture Supporting Independence: Designing an architecture that promotes independence enables teams to develop, test, and deploy with minimal cross-team dependencies, thereby increasing workflow.

Create Conditions to Handle Technical Debt: Technical debt can significantly slow development if not managed properly. Please don't allow it. Build gated check-ins to your pipelines that don't let any code with test coverage less than 80 %, code that fails SAST tests, or code that smells.

When you scale, the flow becomes increasingly important. A single team is usually performing great. The constraints are generally the waste between the teams. Then, we need to remove the constraints to have work move as fast as possible between the teams, that is, flow.

In my experience, we focus a lot on delivery because we resource optimize, and believe we have predictability. This approach only makes us work harder, not smarter. To continuously improve, we should concentrate on reflecting and improving in fast feedback cycles.